What were some of your first creative outlets as a kid?

I was very shy as a child, like extremely shy. I was a perfect nerd in school. My dad was a little bit confused by me because I was very mathematical, I’ve asked my teacher for extra math homework. I have been painting since I was very little. But I never took a specific medium seriously until I pursued photography in my early twenties. Oh, I used to dance as a kid.

That was the first thing that allowed me to feel more confident within myself, not just through my brain, but through my body.

So when did you get your first camera?

I was around my second year of college. I want to say I was 20 or 21. I had held cameras before, but this was my own. I won this like a very budget camera at a raffle in college and it was the only thing I ever won in a raffle. It was this platinum blue Samsung camera. I would always come back to Europe in the summer. I was actually going to Barcelona for the first time and I spent weeks with this little camera. I just followed people around like creepy and observing. When I came back for my third semester of college, I enrolled in my first photography class. I understood that I was very obsessed with people and observing people and the camera was a way of capturing that obsession.

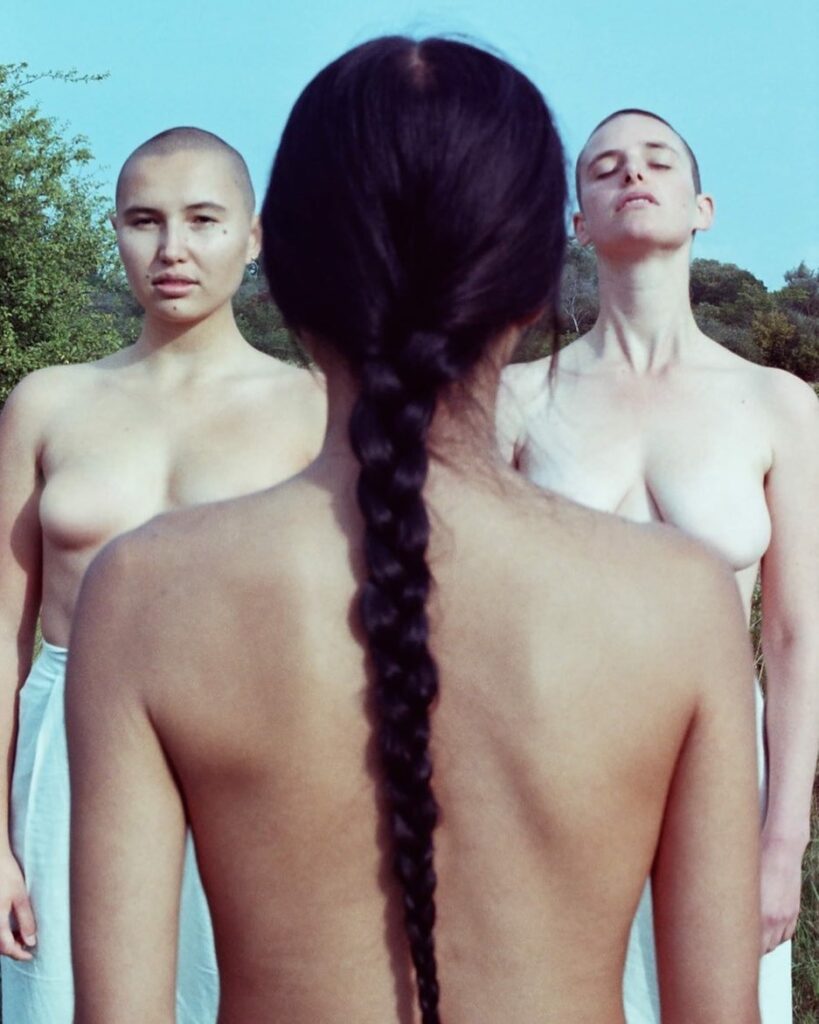

So you just released your new book AGUA, could you give an explanation of the goal you wanted to achieve with the book and describe the visual language used?

I think the book started before I knew it was going to be a book, It was just a series. I feel like that’s how most of my work comes out. There’s something that I’m drawn to or curious about and I start to pursue it. Sometimes I keep on pursuing it more.

It started around a time about three years ago. I had a very strong spiritual experience, an awakening let’s say.

In Ecuador, my aunt is a shamanic woman. She’s a healer. So I think through her, I experienced this deepening into different parts of myself and into my Afro-Caribbean roots. My mother is white and my father is African/Caribbean. I was never raised with my aunt and this was a way to discover, a lot of different realms from my bloodline. After that experience, I moved to Denmark right after. it just became very clear what happened. Two things: I understood that my work had to be more purposeful and second, I developed a deeper relationship to nature and to the way in which I wanted to capture people.

I started to pursue such projects. First, it started with photographing mainly men and water landscapes. At first I couldn’t really grasp why, but my gut was just sending me to these places. I understood that.

I wanted to challenge the way in which men were portrayed, especially brown and black men.

Water allowed me to feel so much for myself. It allowed me to connect in a very profound way. I kind of wanted to translate that and maybe create a space where they can connect. At first I didn’t fully grasp it. I just was just doing it. Later on, I just stopped to reflect and I understood there’s something deeper here and you need to make this bigger. So I went on a quest, and then I just kept on growing the series. Then, I traveled specifically to Uganda, which has one of my favorite water landscapes in the Lake Victoria region. I was consciously pursuing it. These aquatic landscapes and subjects in search of water. I wanted to finish the series in Southeast Asia because I wanted to make a more universal pilgrimage. I wanted to include women and non-binary people or people with albinism.

So you did a lot of traveling in for the book, any memorable trips that you went on that played a big part?

I think that region in the Lake Victoria region and East African Uganda, I mean it compasses three different countries, but I was more focused in Uganda and that really felt like this wonderful, pilgrimage of sorts. I would have a local friend and his father who is a school teacher who used to teach geography. So he just became my assistant. He was like sixty years old and he just became my right hand.

Once we spent eight hours on a motorcycle, three people on it, a small one. Just going through these small communities that live by the water. And that’s what I wanted, to capture people who have a relationship with water. Also, people that didn’t necessarily fear it. There were people who did, and that’s something to bear in mind, even though the photographs were very serene and peaceful, water still is a powerful force. There were people who were absolutely afraid and didn’t know how to swim, but they interacted with it all the time.

Once, to cross one of the rivers, we have to take our motorcycle, with the help of other men, put it on a wooden boat and then cross the river with it floating.

I think those are wonderful memories for me. Really felt like we’re on a quest. I needed like a week to recover because it was, it was very physically demanding. I had to balance my body on top of rocks and there was like a current of water and Ugandan men was holding my arms so I wouldn’t fall on the water. When you’re dealing with nature and unpredictable things in these communities. sometimes having these people just genuinely, spontaneously helped me. That was very beautiful.

What does water represent to you and in the context of the book?

I mean, I see water as a mother figure, that it’s going to nurture you. It’s going to help you heal, but it can also literally destroy you, so you need to respect it.

I think it has that double ability and it is mighty. It can make you carry so much energy and so much peace, but also so much strength and force. I think that it has also been my responsibility and this kind of journey to make people try to connect with it. Because not everyone feels comfortable in water.

I love this idea of creating a space where people can let go. the water facilitates letting go, especially with the men. Can we let go of thoughts and facades. A lot of the time there was an audience that was passing by, they would feel strange by what was happening. Some would begin to laugh actually. So creating a space in which the people in front of you trust you enough, that they can ignore whatever reactions there might be, just there and connecting with me, that’s the most beautiful thing and my favorite part of the process at all times.

What’s a key part of directing your models?

Most of the time I’m dealing with real people and not professional models. A lot of times, they are shocked by why have I chosen them. Sometimes they’re very introverted, sometimes they hadn’t ever really posed in front of the camera, which I prefer.

So they don’t need to hold so tightly onto this image in their brains of how they’re supposed to look.

But that also means I need to direct them a lot just because it’s new for them. I need them to know that I’m there with them and that they’re not alone in this process.

A lot of times I photograph somebody with their dear friend or a sibling, and there’s a relationship between the two. For me, I use this as an opportunity to explore that bond and then challenge them in whatever bond they have.

And I love that. I think when there’s two people who already have a bond, they feel like they’re in it together. So that helps with the directing. I keep it as small of a crew as possible, me and them and maybe one person in the case for translation. For example, some people speak a very specific dialect and even though I could guide them partly in French, there are words, they just will not understand. There’s a lot of body language, but there’s a lot of breathing and eye contact. I think it’s just very much everything. There’s a lot of intimacy. I think intimacy is the most important part for me.

How do we build intimacy?

I think the more I do it, the more I love the process than the actual photos.

The composition of your models are always so unique, and geometric, do you have a picture of what you want to take in your head before you take it?

I think it’s a mixture of things. I think it depends on the subject. depends on the place. I love to to allow the environment to speak to me. I don’t want to control everything. So getting somewhere, and allowing myself to be inspired by what is there in nature and what the light does. We are shooting with natural light and I mostly shoot analog. So you have to be very quick. So sometimes it’s very intuitive. The Ecuadorian sun is just bipolar, very volatile. So you just have to react. You just have to learn how to read people, learn how to move them. Create a mixture of rawness and gracefulness and in between.

Another aspect of the photos that pops out to me is the contrast between the skin tones and the water they are in. Is it important to you to have a variety of tones?

Yeah, I think for me water It’s very universal and it’s very wide-ranging. I wanted to show some diversity within that. Not only with the people but with the types of landscapes and the types of waters. Some are more serene, maybe there’s an intense waterfall. Some are literally in the middle of a city or in a park.

Not every body of water is in this idyllic landscape.

For me, water doesn’t just mean the ocean or like a crystalline lagoon, sometimes the water that was there was extremely polluted. So I think I also wanted to show that water has suffered from human impact. it was a very conscious choice to show different types of water. And I think that I was very grateful to capture also in the Nordics because water takes very different tones there.

Were there any photos that got away?

Oh, but that always happens. This happens almost like 90% of the time where I always think of the photographs that I didn’t take. I visualize after the fact. And then I have to learn to cope with them because I would have become obsessed. But then again, just like, let it go. I just learned that I could recreate that photo in another context. Maybe it was not meant to happen in that context and just learning to not be so harsh on myself.