When the other option is obsolescence or irrelevance, I choose to jump in. Not just because I grew up in the ’80s, weaned on the Atari 2600 and Commodore 64, with the NES as the lodestar of my childhood in 1986. I drifted away when the Z axis debuted in Star Fox in 1993 or so, but still found myself sucked back in over the years—Minecraft, or even mobile war games, like a dweeb. I’ve also been curating exhibitions on this for over twenty years: from getting my college to fund a trip to New York in 2001 to visit BitStreams at the Whitney Museum, to bringing Super Mario Movie by Cory Arcangel and Paper Rad to Deitch Projects in 2004. At The Hole, I think if I curate one more “Post Analog” exhibition someone is going to revoke my curatorial license.

There aren’t enough galleries or museums engaging with this topic—and that lack of institutional support means artists exploring these themes often can’t afford to keep going. If you know how to code, you’ll make more money designing actual games than showing video art in a gallery. The hierarchy of mediums is remarkably weather-resistant: I have to sell scores of paintings to afford shipping a giant video sculpture from France. Even at major museums—like the Buffalo AKG’s recent Electric Op show I visited—early digital works still get barely any exposure. I’ve been chasing this type of work for decades and still feel like I haven’t seen much. Or at least, not nearly enough.

Anyway—this show:

It includes some of the most interesting current art exploring video games’ aesthetics, logic, and cultural impact. “LFG” originated as “Looking For Group” (and aren’t we all?) but these days more often means “Let’s Fucking Go,” the rallying cry of gamers launching a group quest, raid, attack, etc. Multiplayer games, especially RPGs, have made gaming surprisingly social: I had an older brother to play endless hours of Super Mario Kart with in 1992, but years later, coordinating attacks with ten strangers across five continents on a Discord call felt crazy and awesome. Whether storming a dungeon to loot rare armor, healing your tank while dodging area-of-effect fireballs, reviving your squadmate mid-firefight in Call of Duty, dancing on the corpses of your enemies in Fortnite, defending a fortress from Creepers in Minecraft, syncing getaway cars for a casino heist in GTA, or just grinding XP in the desert while getting made fun of—we have found our teams.

Video games have shaped an entire generation of artists—not just visually, but cognitively, emotionally, socially. They’ve trained us to think in systems, to obsess over world-building, to collaborate across vast distances, to inhabit avatars and alternate realities. For many younger artists, games aren’t just a medium—they’re a foundational aesthetic language like cinema or the internet. And it isn’t nostalgia or novelty—it’s infrastructure. The logic of a final boss, grinding, looting, leveling up, and glitching through walls are woven into how we see and make now. For artists raised on LAN parties and lag, boss fights and battle passes, it’s only natural that video games show up in the studio—not just as references, but as frameworks.

At long last, the artists:

Our war team includes Polish trio Bezimienny, Mathew Zefeldt, Kévin Bray, and a wonderful little Bryant Girsch painting titled Battle Boy, where a medieval-helmed fellow reveals his nipple-ringed bare chest. Probing the contrast between human player and game avatar, Bezimienny paints a warrior princess; Zefeldt’s blue babe wields a bow and arrow at a robot while Kevin’s chimeric beast clangs an axe in endless, fragmented motion. Matching Bezimienny’s sculptural little plants are Gao Hang’s First Aid Kits—a relief to refill your stamina after the battle.

Code, light, and glitch are covered by Ksawery Komputery’s interactive, sound-sensitive LED jellyfish Atolla in the rear gallery, and Luke Murphy’s crumpling and slouching LED panels, their custom software endlessly unraveling. Mashine’s painting of a horrifying JD Vance Pikachu is like a glitch in reality—a dank meme culture artifact where lack of oxygen or perhaps hygiene breeds cultural mutants. The nine-screen new AI piece by Tabor Robak also inhabits a dark part of this liminal zone where things go very, very wrong: Dave & Buster’s meets detention camp, as armed guards force prisoners to play strange games.

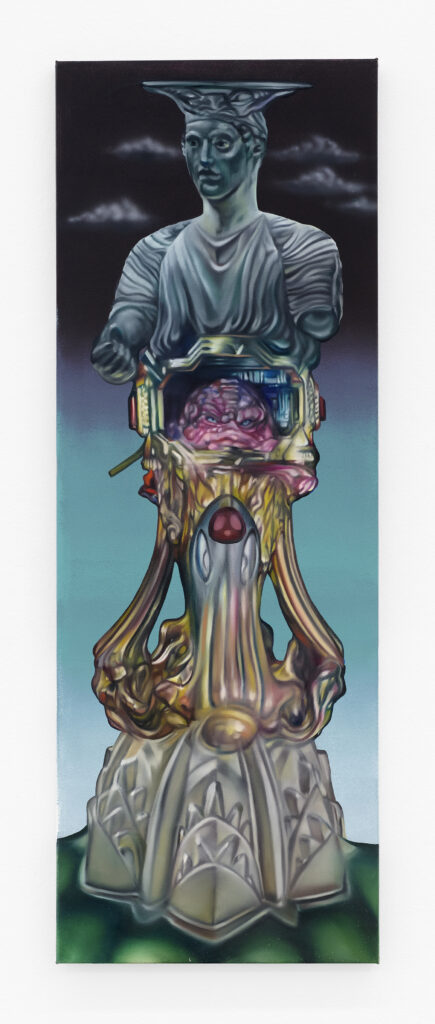

Skin and texture are the focus of Grant Stoops and Magda Kirk, both building figures for battle and leaving them smoothed and unarticulated, skimming them with an iridescent finish or a suit of overlapping tattoos. Botond Keresztesi manages to paint his own unique textures—gilded, pearlescent—to suit a vivid imagination that looks like a computer dreaming.

Janne Schimmel is the only artist to provide us an actual game to play. In a beautiful metal and crystal sculpture, Janne created a strange and boring video game on an old Game Boy—a poetic, odd journey of a little girl in a house, in a forest, with evocative chiptune music composed by the artist. To me, this work encapsulates my own relationship to gaming: forged in 8-bit, seeking materiality, memory, and the poetry that emerges from limited hardware and software. It’s about slowing down the future—resisting obsolescence and skirting death. For people my age, we fell in love with the radical potential of what technology could be. We don’t want to wind back the clock to feel like kids again—we want to go back so we can take a different path: one of hackers and mods, not the morass of social media and corporate gaming culture.

This show is a glimpse of what that path might look like —artists using the tools, textures and myths of gaming not to escape reality but to reprogram it. It’s messy, ambitious and unresolved, like any good game still in beta.